The problem with having a condition, as opposed to an illness, is that it is not what we’ve been brought up to expect. In our childhood we contract various things—from the common cold up to measles, mumps, or an outbreak of salmonella that arrives courtesy of pollution of the city’s drinking water (yes, that happened to me!)—and then what happens? These days, we mostly get over them. We go to a doctor, and the doctor gives us antibiotics, or tells us that whatever it is will subside with a judicious application of broth, tea, and aspirin, and sure enough, in a few days or a few weeks, we feel better.

Yes, sometimes there are lingering effects, and sometimes there are permanent ones, but sooner or later most people get past them or learn to cope.

Having a condition is different. Words like “therapy” and “maintenance” and “pro-active” and “diligence” and “habit” and “routine” suddenly come into your life, and your day-to-day existence begins to be a round of increasingly complex (and sometimes tedious and/or painful) tasks meant to reduce, control, or palliate. And sure, there are a lot of people out there who have far more formidable conditions to contend with—multiple sclerosis, diabetes, Crohn’s disease, the other dreaded C-word—but there are two big differences between what they have and what I do: The first and biggest is that people believe they have a condition or disease; and the second is that individuals and Big Pharma are looking for ways to treat them for it.

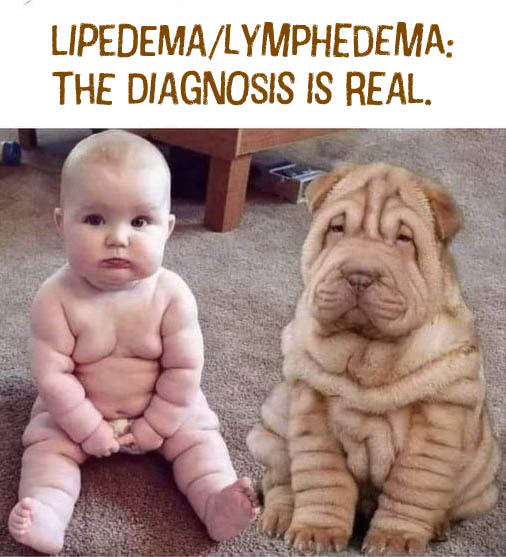

When you have lipedema (and its seemingly inevitable companion, lymphedema), 99 percent of the world takes one look at you and decides that you are a lazy, slovenly, stupid, careless person who doesn’t care about your health. You’re fat; and no one gets fat unless they criminally neglect their health by ingesting things that are bad for them and sitting on their asses instead of getting up and doing something—anything—to move that sluggish body towards thinness.

Not only does no one believe you have a condition, they just assume that you are bringing up this obscure word—lipedema—as an excuse, and that you are lying to them, and to yourself. This isn’t restricted to your family, your friends, and John Q. Public—90-some percent of doctors have never heard of the condition, have done no reading on the subject, and dismiss it out of hand as one more way a patient is trying to wiggle out of responsibility for her own health. They give you a smirk and a diet and send you on your way. It’s an extreme comparison, but it’s kinda like back in the ’80s when gay guys got AIDS and it somehow became their own fault for bad behavior, so no one felt obligated to help them. It was only when it started spreading into the gen-pop that some people took notice and began to work for a cure.

Which brings us to the second thing—almost no one is trying to cure lipedema. There are lots of supposed cures out there for being fat—Facebook is filled with thinly disguised ads for pills and potions and treatments and diet apps to fix your gut and lose that apron belly—but none of them is going to counteract a gene disorder. And since fat is still blamed on the person who carries it, no one is looking.

As a child who inherited my physique (solidly built and curvy) from my father’s side of the family while my mother resembled a waif-like bird with stick arms and legs and was the most fashionable gal on the block, I know what it’s like to be fat-shamed. From the age of 12 when I hit puberty, my mom had me on a diet. We tried them all: Stillman (500 calories a day), the cottage-cheese-and-melon diet, the all-protein-no-carbs route (nobody knew to call it keto in those days), you name it and we did it. She always had a mythical five pounds she wanted to lose from her tiny pooch belly that she retained following pregnancy, while I was to set my sights on the figure of a supermodel. In my sophomore year of high school I was 5 feet six inches tall and weighed 126 pounds, but mom wanted me to weigh the same as cover girl and Partridge Family daughter Susan Dey, who clocked in at 112. (In later years Susan revealed that she was bulimic during those halcyon days.)

It took me until my 30s (and ridding myself of a husband who also fat-shamed me) to get past the cycle of yo-yo dieting and decide that I would simply be there for my own health. I became a vegetarian, baked my own bread, and took up running, which I had pursued for a brief stint in college. I started out with half a mile and worked myself up to three miles a day around a nearby golf course with a track along its perimeter. I rode my bike as well, and began to see muscles bloom where none had shown before. And still, with all that, I was plagued by the sense of my own inappropriate bulk. I have a dress I bought during those days, to wear to a big party at my office to celebrate 50 years of publishing The Advocate; it was a size 8, and still, I felt self-conscious. I look back at my life now with such regret for the time I wasted between 12 and 48, worrying about the way I looked instead of realizing how beautiful I actually was, and allowing myself to enjoy life.

I denote 48 as a turning point because that’s when I began my third career as a librarian and did actually fall into bad habits that caused weight gain due to carelessness and sloth (although those characteristics were lacking when it came to my work!). I was putting in about 48 hours a week and commuting 45 minutes one way, so unless I wanted to rise an hour earlier or exercise in the dark after work, my daily two-mile walk was out. My job was stress-laden enough that as an introvert who had forced myself into an extrovert’s profession, I badly needed my lunch hour alone to decompress, and the best way to get that time was to go out, so I went to cheap restaurants and ate more fried food than I had in decades. My weight began to climb, and although it was at an almost unnoticeable rate of about five pounds per year, do that for more than a decade and see what happens. I began having problems with my feet, my knees, and my back, not helped by a couple of falls and a car accident, nor by needing to go on a blood thinner after a couple of clots appeared in my right leg.

When I retired, I weighed 125 pounds more than I wanted to—and my expectations for the proper weight were, by this time, real, not idealized. But I thought I could take care of things pretty easily, now that I wasn’t stressed by supervisors’ meetings, or unable to find time to cook for myself or exercise. I paid a visit to my doctor for a weigh-in, had blood work done, got on a couple of vitamins in which I was deficient, and set out to change my physical being back into someone I recognized. For the next four months I cut out the fried food, cooking myself wholesome meals and limiting the desserts, and took up my walking regimen once again. At the end of that period I went back to my doctor, expecting to surprise him and myself with a significantly lower BMI, and instead discovered that I had put on another 30 pounds. In four months.

My doctor flat-out accused me of “lying to myself” (what he actually meant was lying, period). I explained my new regimen at great length and wondered if the blood thinner might be to blame (there was anecdotal evidence), but he wasn’t interested; he handed me a diet sheet and told me to check back in another three months.

This is when my cousin Kirsten, the member of the family who really should have been a research librarian, began to poke around and thus discovered lipedema. After having read a list of the characteristics and symptoms (pear shaped, with prominent thighs, shelf butt, and cankles, with inexplicable weight gain), she advanced the theory that this might be something I should examine. Ultimately it brought us to a lipedema/lymphedema specialist in Santa Monica, who confirmed that I did, indeed, have both.

Unfortunately, it also yielded up the information that there wasn’t much I could do about it. We read that lipedema was caused by a fat-storing gene that wasn’t affected by diet and exercise; yet the lipedema specialist told me I should pursue both of those, and gave me yet another diet whose severity (no gluten, no eggs, no sugar) brought back every triggering moment of my childhood. Given all the research, which said the only solution for lipedema was surgery to remove the calcified fat deposits, I eyed the doctor’s regimen with a jaundiced eye and didn’t pay it much mind. Why should I suffer if it wouldn’t yield any results?! Also, my time and attention were more urgently focused on the secondary condition, the lymphedema.

The lymphatic network is the most powerful one in the body, ridding it of waste in a passive system that moves fluid in the opposite direction from gravity. The fluids proceed upwards through the knees, the groin, the abdomen, and the armpits to the collarbone, location of the subclavian vein, where they are dumped back into the bloodstream after absorbing dietary fats in aid of metabolization, and the liver and kidneys go to work to eliminate the leftover waste. Interrupting or damaging the lymph system can be catastrophic for continued good health, and lipedema is one of the things that can interfere with a healthy lymphatic system, because the calcified fat blocks off lymph circulation and pushes the fluid to the surface of the skin.

Because of the aforementioned gravity, the effects of lymphedema are mostly felt in the legs and feet, where the liquid pools when the lymph system has failed to carry it upwards to the bloodstream, which is pumped by the heart. The legs swell up, and feel heavy and sometimes painful to the touch. The skin roughens, and becomes increasingly vulnerable to small wounds that, if there is enough lymph fluid present, can leak it directly out onto the surface of the skin, a condition known as lymphorrea.

During the next three years, I kept gaining weight. The more I gained, the harder it became to exercise, and the less exercise I got, the worse the lymphedema became. The thing that I finally (recently) realized is that the diet-and-exercise regimen isn’t to interrupt the lipedema (it won’t) but to keep the lymphedema at bay, and I was not being successful at that. So I am now eating a “clean” diet, trying to wrap my ADD head around the necessity to drink large quantities of fluid every day, and slowly and painfully incorporating more exercise into my routines.

Meanwhile, however, both the physical and psychological aspects of these two interrelated conditions are taking a massive toll. Imagine growing up as a child who was constantly made to feel self-conscious about their weight, shape, and size, only to be afflicted in old age (and not that old) with a condition that emphasizes all that beyond your wildest nightmares. Imagine doing art workshops at libraries and having to email ahead to request that they find you a chair to sit in that doesn’t have arms and is sufficiently sturdy to hold your weight. Now imagine having to do that as well every time you visit a restaurant—or any public place where you’d like to sit down but can’t because you don’t fit in the chairs. Going places like the movies or the theater becomes out of the question. Flying anywhere on a trip necessitates traveling business class so your butt fits in a seat. And imagine all of that endured, along with the pain to your knees and feet of the accompanying lymphedema, under the judgmental eyes of everyone who sees you as ugly, laughable, or as an object of disdain and disrespect. You’re FAT. What’s wrong with you? Why don’t you DO something about it?

If they only knew. The daily regimen for someone with lymphedema is extensive. If your legs are leaking, you must clean and bandage them, put a sleeve over the bandage and then a compression stocking over the sleeve. Daily lymphatic massage, for a specific duration and in a certain order from collarbone to toes, is a necessity. Additional exercise of some sort is recommended, if you have the energy and can deal with the numbness in your feet, the sudden stabbing nerve pain in your legs, the bad knees and spasm-y lower back that result from walking bent over with a cane. Getting around is difficult, yet you must be persistent in fetching and carrying water and/or other fluids to drink, in whichever room you end up. You can’t sit for too long without everything stiffening up, so you tend to set alarms on your phone to remind you not to spend hours at the computer or painting or reading—whatever sedentary occupation previously occupied your time—and your focus suffers. Simple tasks become complex challenges because you can’t lift much with one hand, but need the other to support your weight on your cane. All the extra fluid you are carrying in your body—sometimes estimated at as much as 50 pounds per leg—makes you tired and out of breath, so you do one thing and sit, do another thing and sit, and think hard when moving from one room to another to see if you can put things in pockets or sling them around your neck so you don’t have to make multiple trips.

Food is a challenge, because you have to be assiduous about reading labels and avoiding the many triggers of inflammation. You also have to prepare it, when you find it hard to stand for more than three minutes unsupported or more than 10 with one hand holding you up. You long to just access DoorDash on your computer and order something from a local restaurant, but don’t want to pay the high price of takeout and delivery with the equally important high price of possible inflammation from ingesting unknown ingredients.

Washing and drying your hair, bathing, and dressing in outdoor clothing become exhausting routines that you avoid unless you absolutely must go out that day. Everything takes twice as long as it used to, and makes you tired before you set one foot out the door. Driving is hard on your swollen legs and feet. Heaving a walker in and out of the trunk of your car becomes increasingly wearisome. And the cloud above all of this is having to do it in the public eye, feeling as you do about your enormous physical presence.

In my previous post about this I talked about giving in to the demands of the body, accepting the routines, making the plan, exclusively pursuing the remedies. About coming to terms with the fact that, from now on, this will be my job. I think I have come closer to that in the intervening days, as I see the effects of the alternative (ignoring the problem and hoping it will go away). But I have to say that it would be nice if I could wear a (super lightweight) sandwich board over my shoulders with a sign fore and aft that says “It’s lipedema! That’s a real condition!” Perhaps the next step will be the ability to give up on the idea of accountability, ignore the reactions of others, and either become serene within the confines of my truncated existence or learn to push the boundaries in new ways.

In either case, thanks for listening. I needed this.

Leave a comment